“Adoption is a redemptive response to the tragedy that happens in the broken world.”

— Katie J. Davis

The article encompasses the Indian Laws and guidelines established to process adoption with the help of case laws as per the religion of the people of India.

Introduction

Adoption is a worldwide followed, beautiful practice of providing a home to unprivileged children. It refers to the permanent legal transfer of parental rights to the adoptive parents. Thereby leaving no difference between the rights of a biological parent and that of the adoptive parent. An adoptive child has all social, legal, emotional, and kinship benefits as of biological child. Once the process of adoption has been completed lawfully it cannot be held null and void.

The practice was initiated to serve humanitarian purposes. However, later the intent involved the satisfaction of the natural desire of having children. Before 1926, adoption was not recognized as a legal concept, i.e., no legal framework had existed for adoption. The first adoption law, The Adoption of Children Act, 1926, was passed by England and Wales. The main reasons to enact such legislation were the aftermath of World War I and the influenza epidemic, due to which numerous children were either abandoned or were separated from their biological parents. The purpose was to prevent the biological parents from claiming back their children and to protect the rights of the adopted child in their new families.

Later, in 1950, a more comprehensive act was conceded for fulfilling the requirements of a legal framework for governing adoption in that period. However, it was later again modified in 1958. Many countries realized the need for such legislation after World War II. Consequentially, between 1940-1980, an enormous number of countries enacted the adoption laws.

Adoption In India

India, being the land of numerous religions, comprises broadly four sets of personal laws and one secular law. Adoption is an ancient old custom practiced in India with variable objectives. It began from the humanitarian motive of caring and bringing up a neglected or destitute child and has stretched to a natural yearning for a kid as an heir after demise, an object of affection and a caretaker in old age.

Since the act of adoption comes under the ambit of humans family matters i.e., personal laws, people belonging to different religions are governed by different personal laws on the matter of adoption as well. Indian citizens who belong to Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, or Buddhism, are allowed to formally adopt a child i.e., the concept of adoption has been recognized expressively in their laws. The Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act of 1956, was incorporated the Hindu Code Bills to govern the matters of adoption and maintenance. Whereas, on the other hand, the personal laws of Muslims, Christians, Parsis, and Jews do not recognize such practice.

It is considered that adoption does not exist in Islamic law as it does in Hinduism. The Muslim personal law neither specifically provides a provision for adoption, nor does specifically prohibits the practice. A similar concept, to that of adoption, exists in Islamic law, i.e., Kafala which means ‘sponsorship’. It is more like the concept of the foster parent relationship.

Hindu Law

Under the Hindu personal law, people belonging to the religions recognized by the said law are governed by the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956 for the adoption of a child.

Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956:

(hereinafter HAMA)

It deals with subjects such as the essentials of valid adoption, capacity to adopt, capacity to give in adoption, who can be adopted, effects of adoption, etc. It allows both males and females with similar capacities to adopt a child, provided they fall under certain criteria set by Indian laws for adoption. After the amendment act of 2010, Hindu females have been given equal rights to adopt a child as that of Hindu males.

S. 6 Requisites of a valid adoption

No adoption is said to be valid unless the-

- one adopting has the authoritative right to take in adoption;

- one giving in adoption has the authority to do so;

- the adopted person is capable of being taken in adoption;

- Adoption is made in obedience to the other conditions mentioned in Chapter 1.

S. 7: Capacity of a male Hindu to adopt |

S. 8 Capacity of female Hindu to adopt |

| Any male Hindu who is,

a) Sound-minded b) Not a minor Provided if he has a living wife, her consent is mandatory for adoption, unless she falls under the following disqualifications:

|

Any female Hindu who is,

a) sound-minded b) not a minor c) who is unmarried, or if married, her marriage has been dissolved or whose husband is dead or he falls under the following disqualifications:

|

If a person has more than one wife living at the time of adoption, the consent of all the wives is necessary unless the above exceptions are to be applied. In the landmark case of Ghisalal v. Dhapubhai[i], it was held that the consent of the wife is mandatory in adoption. It should either be in writing or reflected by affirmative/positive act voluntarily and willingly done by her. Consent of spouse cannot be inferred mere presence, silence, or lack of protest.

In the case of Brajendra Singh v. State of Madhya Pradesh and Anr.[ii], the Supreme Court demarcated the thin line difference between S. 7 and S. 8 of HAMA. It was stated that unlike the proviso to S. 7 which bars a male Hindu from adoption except with the consent of the wife unless she is under a disqualification stated therein, S. 8 does not require the consent of the husband if the wife has the requisite capacity. Conversely, if she does not have the capacity as per S. 8(c), consent of the husband cannot clothe her with such capacity.

S. 8(c) of the Act brought about a very important and far-reaching change in the law of adoption as used to apply earlier in the case of Hindus. It is now permissible for a female Hindu who fulfills the conditions states in S. 8 to take a son or daughter in adoption to herself in her own right. It follows from S. 8(c) that a Hindu wife who does not meet the capacity requirement therein specified cannot adopt a son or daughter to herself even with the consent of her husband because the section expressly provides for cases in which she can adopt a son or daughter to herself during the lifetime of the husband.[iii]

S. 9 Persons capable of giving in adoption

- No one except the father/mother/guardian of a child shall have the capacity to give the child in adoption.

- Father/mother, if alive, shall have equal rights regarding the same. Consent of both is mandatory unless the other falls under aforesaid exceptions.

- Guardian of the child is authorized to give him in adoption with the permission of the court if both his parents are dead or condition similar to aforesaid exceptions.

S.10 Persons who may be adopted

- S/he is a Hindu;

- S/he has not already been adopted;

- S/he has not been married;

- S/he has not completed the age of fifteen years.

S. 11 Other Conditions for Adoption

- If adoption is of a son: Adoptive parent must not have a Hindu son, son’s son, or son’s son’s son living at the time of adoption (neither by blood nor adoptive)

- If adoption is of daughter: Adoptive parent must not have a Hindu daughter or son’s daughter at the time of adoption (neither by blood nor adoptive)

- An adoptive father must be 21 years older than an adoptive female child and similarly, an adoptive mother must be 21 years older than an adoptive male child.

- A child cannot be adopted by two or more persons simultaneously

- A child to be adopted must be given and taken in adoption with intent to transfer by parents/guardians to the family of its adoption.

The performance of data homam is not an essential condition for the validity of the adoption.

In the recent judgment of M. Vanaja v. M. Sarala Devi[v], the apex court held that compliance with the conditions in Chapter 1 of the 1956 Act is mandatory for an adoption to be treated as valid. The two important conditions as mentioned in S. 7 and 11 of the HAMA are the consent of the wife before a male Hindu adopts a child and proof of the ceremony of actual giving and taking in adoption.

S. 12: Effects of Adoption.

On adoption, adoptee gets transplanted in adopting family with the same rights as that of a natural-born son. The adopted child becomes coparcener in Joint Hindu Family property after serving all his ties with his natural family.[vi] The adoptive child also acquires the caste of his adoptive parents which will be treated as his caste by birth.[vii]

- All old ties with the birth family shall be severed and replaced by new ties with the adoptive family.

- An adoptive child can’t marry a person who s/he could not have married before adoption.

- Property of the adoptive child which vested in him before adoption shall continue to vest in him. Obligations attached to the property will also remain.

- Such child shall not divest any person of any estate which vested in him or her before the adoption.

The Guardians And Wards Act, 1890

Since personal laws of Muslims, Christians, Parsis, and Jews do not recognize complete adoption, the non-Hindus, belonging to such religions, willing to adopt a child can take the child in ‘Guardianship’ under the provisions of The Guardians and Wards Act, 1890. The process makes the child a “ward”, not an adoptive child. He attains individual identity on turning 21 years of age and no longer remains ward. S/he doesn’t have the automatic right of inheritance. However, such parents can gift it to him.

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015

People belonging to religions that are not recognized under HAMA can opt for complete adoption under this act, as HAMA already provides for complete adoption for people belonging to the Hindu religion.

- 2 (2) defines ‘adoption’ as the process through which the adopted child is permanently separated from his biological parents and becomes the lawful child of his adoptive parents with all the rights, privileges, and responsibilities that are attached to a biological child.

Chap. VII of this act, “Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration” is indeed a respectable approach of the legislator to secularize adoption and a positive step towards the welfare of abandoned, orphan, and surrendered children. Adoption has been included as one of the methods for social integration and rehabilitation of children. “Restoration and protection of a child” means restoration to— (a) parents; (b) adoptive parents; (c) foster parents; (d) guardian; or (e) fit person.[viii]

Chapter VIII of the said Act deals explicitly with the concept of adoption. S. 58 of the Act deals with the procedure for adoption by Indian prospective adoptive parents living in India. It unambiguously suggests that the procedure is to be followed “irrespective of such prospective parent’s religion”.

Inter-Country Adoption

In Re Rasaiklal Chhaganlal Mehta[ix], the court held that inter-country adoptions under S. 9(4) of HAMA, 1956 should be legally valid under the laws of both countries. The adoptive parents must fulfill the requirements of the law of adoptions in their country and must have the requisite permission to adopt from the appropriate authority thereby ensuring that the child would not suffer in immigration and obtaining nationality in the adoptive parents’ country.

In the landmark judgment of Lakshmi Kant v. UOI[x], the lack of regulation of intercountry adoptions in India which might lead to the trafficking of children was pointed. A magazine called “The Mail” was published stating the deteriorating condition of children who are adopted from India and then transported for malpractices like child trafficking and child abuse etc.

A comprehensive framework was formulated for regulating intercountry adoption to protect the children and provide them healthy family life.

The international adoptions were made to follow the regulations of the Guardians and Wards act, 1890. Article 15 (3), 24, and 39 of the Indian constitution were used as a reference along with the UN declaration on the rights of the child. It was made mandatory for the foreigners who wish to adopt Indian children to be sponsored by licensed agencies of their own country.

The apex court held that in case of violation of the principles and guidelines, the adoption would be declared invalid and the person at default would face strict actions against him/her.

Central Adoption Resource Agency

CARA was set up by the government with branches in different areas to facilitate easy adoption across the country. They also published guidelines for the same.

It is a statutory body that falls under the ambit of the Ministry of Women and Child Development. It functions as a nodal body for the adoption of Indian children and is mandated to monitor and regulate in-country and inter-country adoptions. It is designated as the Central Authority to deal with inter adoptions as per the provisions of the Hague Convention on Inter-country Adoption, 1993, ratified by the Government of India in 2003.

CARA Guidelines

Who can adopt

- A single male or female or married couple(resident of India) ;

- A non-resident Indian/ overseas citizen of India;

- Foreign citizen.

Some of the most important and basic guidelines by CARA for eligibility to adopt a child are mentioned below:

- The prospective adoptive parent must be emotionally/physically/mentally stable and financially stable must not have any life-threatening medical condition.

- Irrespective of marital status and presence of biological son/daughter, one can adopt a child subject to the following conditions:

- In the case of a married couple, consent of both spouses is required,

- A single female can adopt a child of any gender,

- A single male cannot adopt a girl child.

- In the case of a married couple:

- Two years of stable marital relationship

- Composite age of prospective parent to be counted

- Won’t be considered for adoption if have three or more children u=except in case of special need children

- The minimum age difference between the adoptive child and either of the prospective parents must not be less than 25 years.

- Age criteria are not applicable in Step-parent adoption.

Eligibility of a child for adoption

Point 4, Adoption Regulation, 2017

(a) Any orphan or abandoned or surrendered child, declared legally free for adoption by the Child Welfare Committee; (b) a child of a relative defined under sub-section (52) of section 2 of the Act; (c) child or children of a spouse from an earlier marriage, surrendered by the biological parent(s) for adoption by the step-parent.

Eligibility criteria for Prospective adoptive Parents by CARA

Adoption Procedure for Resident Indians

Adoption Procedure for NRIs, Overseas Citizen of India, And Foreign Prospective Adoptive Parents

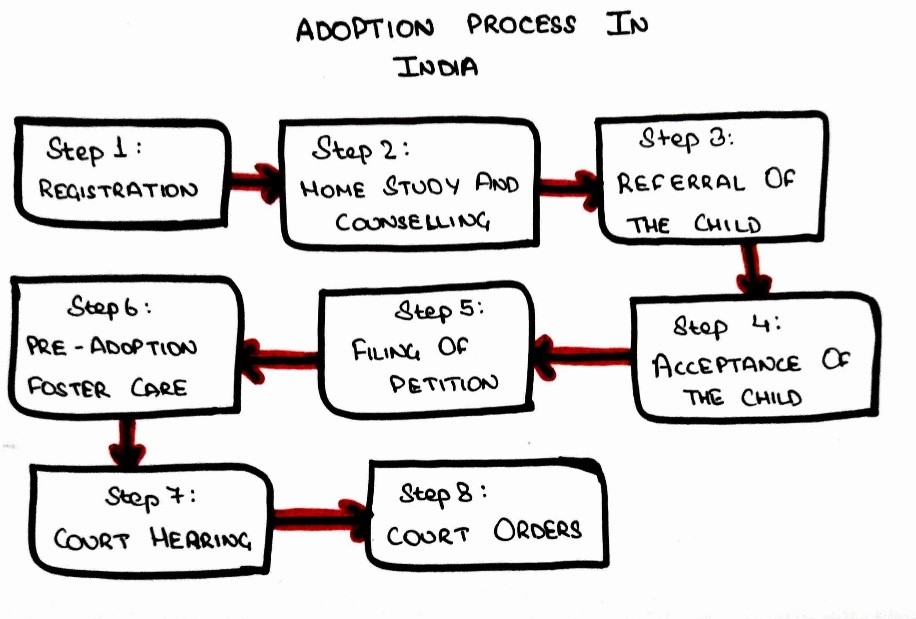

Process of Adoption

- The Specialized Adoption Agency (SAA) nearest to the parent’s address will conduct a Home Study of a prospective parent. The parent will become eligible for receiving a profile of the child only after the Home Study Report (HSR) is uploaded in CARINGS.

- The parent can see the entire profile and medical history of the child in the referral.

- The parent can then choose to Reserve or Not Reserve a child within the stipulated time of 48 hours.

- Upon reserving, the child has to be accepted within 20 days. Parents who do not accept the child in the above period will be relegated to the bottom of the waitlist.

- Parents who do not accept any of the three profiles will be relegated to the bottom of the waitlist. However, their registration shall continue to be valid, with revalidation of the HSR every three years. A predefined amount is to be payable to the SAA which includes expenses for home study, legal services, etc.

Adoption by Step-Parent

It is also known as second-parent adoption. Through this concept, a stepfather/mother can make new ties with the stepchild as that of a biological father/mother. The procedure for stepparent adoptions is comparatively faster and easier than other kinds of adoptions in most states. Where a non-family member has to adopt a child, s/he has to follow an exhaustive procedure including screening procedures, such as in-depth interviews, home studies, background checks, and other things. However, in the case of stepparent adoptions, some states do not require much investigation into the situation, especially if the child is already living with the stepparent or second parent. Certainly, stepparent adoptions go faster than other types of adoption and are less expensive.

Adoption procedure for Step-Parents

Is it hard to adopt a child in India?

One can conclude through the process of adoption itself that adopting a child in India is not a cakewalk. Relying on the testimonies on the internet regarding the adoption of children depicts that it is indeed a tedious, prolonged and hectic process to accomplish. As it comprises numerous steps, procedures, and criteria, it often becomes problematic for the prospective parent to adopt a child lawfully in India. The long duration of completion of all the legal procedures tends them to go for the middlemen’s option and makes them pay a hefty amount to choose a hassle-free method for adoption. However, considering the rate of offenses against children, the need for an appropriate solution has arisen, thereby leading the Govt. of India to enact such hard procedures to ensure the utmost safety of the children of the country.

Landmark Cases

Shabnam Hashmi v. Union of India

In Shabnam Hashmi v. Union of India[xi], it was put forward that personal laws of Muslims, Christians, and Parsis do not recognize adoption laws, therefore they have to approach the court under the Guardians and Wards Act, 1890. The Apex court held that non-Hindus can also adopt children under the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015.

Lakshmi Kant Pandey v. Union of India

In Laxmi Kant Pandey v. Union of India[xii], a PIL was filed against the malpractices in the name of inter-country adoption. CARA was formed. (The case has been discussed earlier under the subheading “Inter-country Adoption”)

Rahasa Pandiani by Lrs. v. Gokulananda Panda

In Rahasa Pandiani by Lrs. v. Gokulananda Panda[xiii], it was held that when there is a claim for adoption then the same has to be proved by way of clinching evidence. An oral adoption must be presented with some documentary evidence that could dispel the clouds of uncertainty.

Shrinivas Krishnarao Kango v. Narayan Devji Kango

In Shrinivas Krishnarao Kango v. Narayan Devji Kango[xiv], the Supreme Court held that in cases where a child is adopted, the effect of adoption is such that it creates a legal fiction and the child becomes a legal heir. When adoption is made by a Hindu widow, the effect of adoption is such that it relates and makes him eligible for all the rights of a son from the date of death of the father.

Conclusion

As the concept of adoption has been proved to change the lives of millions of children for a noble cause, one cannot neglect the threat it poses to the lives of those children. In the era of human trafficking and child abuse, it is all the more necessary to formulate effective laws to not only help the little lives but the families as well to provide them with a method to complete their families. Since adoption deals with such a sensitive part of human life, the legislators have to be much more careful while formulating such laws. As its objective has changed with the passing time, threats and abuse of such laws are also mutable, thereby making it necessary for legislators to incorporate amendments for its better application. Therefore the laws and procedures regarding adoption are not easy to comprehend by a layman.

Current adoption laws in India do not recognize adoption by same-sex couples. However, it has been already allowed in countries like Spain, Belgium, etc. The Navtej Singh Johar judgment was a major step towards the upliftment of the position of the LGBTQ+ community in society but still, a lot is required to be done by both the judiciary and the legislature. The state should not only legalize same-sex marriages but should also amend the existing laws to provide legal recognition to adoption by same-sex couples.

FAQs

Can a single male/female adopt a child in India?

Yes. However, s/he must abide by the CARA guidelines formulated by the Govt. of India.

Can a single male adopt a girl child in India?

No. As per the CARA guidelines 2017, a single male is prohibited from adopting a female child.

Can a single female adopt a male child in India?

Yes.

Can a Foreign citizen/ NRI/ Oversea citizen of India adopt a child in India?

Yes. However, s/he must abide by the CARA guidelines formulated by the Govt. of India.

What is the minimum age difference between the adoptive child and either of the prospective parents required as per the adoption norms in India?

The minimum age difference between the adoptive child and either of the prospective parents must not be less than 25 years.

Are age criteria formulated under CARA Guidelines applicable in Stepparent adoption?

Age criteria are not applicable in Step-parent adoption.

Which government body regulates adoption across the country?

Central Adoption Resource Agency

Relevant Links

Eligibility criteria for Prospective adoptive Parents by CARA

Adoption Procedure for Resident Indians

Adoption Regulations, 2017

Adoption Procedure for NRIs, Overseas Citizen of India, And Foreign Prospective Adoptive Parents

Adoption procedure for Step-Parents

[i] AIR 2011 SC 644: (2011) 2 SCC 298

[ii] (2008 13 SCC 161 : 2008 SCC online SC 109

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Point 4, Adoption Regulation, 2017

[v] (2020) 5 SCC 307

[vi] Basavarajappa v. Gurubasamma, (2005) 12 SCC 290

[vii] Khazan Singh v. Union Of India AIR 1980 Del 60

[viii] S. 40 Restoration of Child in need of care and Protection, JJ Act, 2015

[ix] AIR 1982 Guj 193

[x] AIR 1984 SC 469

[xi] AIR 2014 SC 1281

[xii] AIR 1984 SC 469

[xiii] AIR 1987 SC 962

[xiv] AIR 1954 SC 379